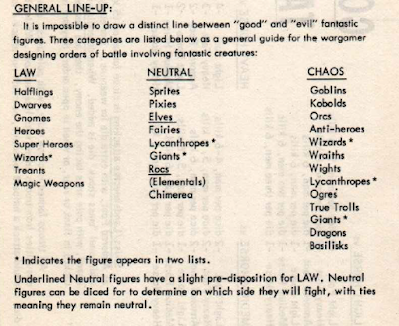

Time for another review! And since I just finished re-reading Muster, let’s talk about it! This is going to be a bit more rambling as a review than the two modules I did, because, well, it’s a different kind of book!

|

| Muster cover art. |

Overview

Muster is a rather interesting read, as it is not really an RPG book or a module. Instead it’s a book of theory and advice on how to place D&D in what the author calls “the wargaming way” - a style of play similar to or adjacent to OSR play, though with some interesting peculiarities. This puts it in a similar category to Philotomy’s Musings, or perhaps smaller works like the Old School Primer by Matt Finch and the Principia Apocrypha.The book was written by Eero Tuovinen and illustrated by Sipi Myllynen. I am not sure who did the layout and editing, but it is published by Arkenstone Publishing so…someone from there, presumably?

What works for me

Let’s try and go over some of the things present in the book, because there’s a lot. The book begins by laying out first off what is meant by “wargaming way”. It is a curious term, as it refers to the old Prussian kriegsspiel which are generally seen as the progenitor of civilian hobby wargames that came in the century or two after it.

On one hand, it is rather odd why this term was chosen, as opposed to simply using the much more popular label of OSR. However I think since this method of play was developed within a relatively small group of Finnish gamers (from what I can gather from the text at least), I think it is also okay to give it a distinct name.

Next up the book presents the basic tenets of the Wargaming Way of play, divided into a Basic Outlines portion and an Advanced Matters portion. The Basic Outlines covered are things one can find in the other theory or instructional texts that I linked above - do not fudge dice rolls; always start at 1st level; the importance of the campaign as a coherent world rather than an individual character or party of characters; goal-based XP (usually 1 exp point for 1 gold. We’ll get to this later); player-driven gameplay and general disregard for formal rules texts in any situation where they do not actively contribute to helping run the game.

One thing that is a common feature of OSR pedagogical texts and has become a common mantra, and yet is missing from this text, is the whole “combat is a fail state” declaration. The book does not seem to agree, with that combat is in fact often the entire point of the specific scenario or situation set up by the GM for the players, and figuring out how to tackle it in a way which can lead to victory may be the entire point.

The book also covers stuff like Dungeon Doctrine and how a group can go about developing it - how to open doors, how to explore corridors, how to react to given situations. The kind of play that groups playing in high-lethality dungeon crawling scenarios tend to quickly learn how to do simply so they don’t just get wiped out every 10 steps.

There is also advice for the GM on how to set up this type of game, denoting two forms of campaign - the basic and extended campaign. The basic campaign consists of simply picking a module, running players through it, then picking another one, and then another one and so on. The extend is what is commonly called “sandbox” play where you have a wide open world through which the players are free to explore and direct the game.

I do wish the book actually went into a bit further detail on how to actually do the work of organizing this however. Of course every Referee’s workflow on preparing a campaign is slightly different, but outlining good common practices to keep in mind like how to organize players, how to keep track of time, location and note taking, how to incorporate modules that do not quite fit with your world’s setting into it - those are all good pieces of advice I think would have fit quite well within this book.

Next up a thing that I like is a small chapter titled D&D and Chauvinism which covers D&D’s ties with adventure fiction of the early 20th century and the implication that has for what kind of stories D&D tends to replicate - tales of colonialism, imperialism and so on. If you’ve read anything by Traverse Fantasy or Zedeck Siew you probably already know all this stuff. The book also does come to the same conclusion that I have come to regarding all of this, which is that attempting to seek some kind of political (or god help you, moral) purity through playing elfgames is probably misguided and it’s a lot simpler to just acknowledge that the characters in these games are, well, amoral (if not immoral) assholes.

The inclusion of this chapter is one I feel was a good call. While it is mostly unrelated to the rest of the text and feels a bit shoved and out of place…that’s also kind of the point, I feel. It acts as a good stopping point for the various flavors of self-deluded reactionary elements in the OSR. And anything that reminds those people that they’re fucking idiots is alright by me!

Other things of note - the text comments on experience points and their importance to the wargaming method on numerous occasions. It instructs using exp as more or less a victory points score in an old arcade game. An indicator of how far you’ve gotten and how well you’re doing in the game. The book is very very clear that experience points should be earned through clearly predefined goals, and not as participation awards or awards given for doing any out-of-game activity.While I do agree with this sentiment to some degree… I also give experience in my current campaign for numerous activities such as carousing, players doing mapping, acting as a quartermaster or as a caller or writing session reports. However my reasoning behind giving experience of those things is that that experience acts, in its own way, as a teaching tool - it rewards what I consider good practices for players in an OSR play style.

An interesting aspect of this approach to XP is that I did not find anywhere in the book a mention of giving experience points based on enemies defeated or killed. The only concrete example is giving exp for treasure retrieved (the typical 1 gp = 1xp practice found in a lot of OSR games). I am not sure if that is a deliberate omission or simply one that was not mentioned but still used. The whole “goal-oriented exp” thing is also something I’ve been thinking about as well in my own campaign. In the session where my players were attempting to break into and disable the garrison of a gatehouse I had decided early on that they were not going to receive experience points for killing the guards or the loot they foud in the gatehouse, as giving experience for that means that the next logical step would be simply murdering people in the streets for exp too. However, as you see in the Observations part of that session recap, I also in the end decided to grant the party exp based on the fact that they had a specific goal for this session and they managed to achieve it.

So I suppose I do see the value in goal-based experience points, however this is another case where I wish the book actually laid out a much more practical example of “This is how this Referee in our game used experience points” and lay out what kind of goals were used in the game as well as what kind of experience points were given. I suspect not a lot of exp though, considering that the book says that getting a character from level 1 to level 2 takes about 10 to 12 sessions of play!

There are a few “war stories” sprinkled throughout the book of various players from that play group discussing situations that occurred in the campaign(s?) they’ve played in over the last few years, and used as illustrative examples of the wargaming way. They’re neat, and also can easily be skipped which I think is probably the best way to handle these types of stories. They did, however, offer some amazing bits of writing like the party in one game deciding they will bring down a group of body-possessing witches by…framing them for witchcraft. Or the curious cultural touchstone of the module B9 Caldwell and Beyond and its place in Finnish D&D culture.

The last thing I’d like to single out to comment on is what the author terms the Nihilistic Void, which is the strange situation that results in this style of gameplay - the fact that the Referee, despite moving the enemy pieces, should ideally not actually play as an enemy of the players. Which then means that the players simply are struggling against the void of failure itself. The book spends a few pages discussing the implications of losing characters and the emotional impact it has, and I’ll admit that this is something that I’ve struggled with on how to handle as a referee myself.

There is a lot of good in this book, and honestly, for me to cover all of it would be to essentially write a very messy synopsis of every chapter, so let’s move on.

What doesn’t work for me

I have only one main criticism of the book, and that’s to do with layout. While the actual text itself is laid out perfectly well and is easy to read, at some point there was an odd decision made to include these pages of schematics which are, at least in theory, supposed to visualize what the text around them is talking about.

|

| This is not really helping. |

However the issue with them is twofold. First off they just kind of don’t do a good job at actually explaining the text in a visual way, and I personally found the more confusing than the actual body of the text, not less. Secondly, they are inserted often right in the middle of a chapter, basically splitting the text from one page to another, which is not unreadable ro anything, but definitely a baffling layout decision regardless. For my money, they could have easily been moved around to split the text between chapters or topics…or just outright dropped.

The layout issues continue with the fact that the Table of Contents is not really in the beginning of the book. Instead there is a manifesto of sorts for the wargaming way, and only then do you get to the table of contents. I personally would have switched them around.

Lastly, the artwork in the book. The book actually has a surprisingly high amount of art, and some of it in full color (so are the pages of visual aids too, as you can see above). Meaning no disrespect to the artist who illustrated the book, most of this art could have simply been cut. While the actual style of the illustrations itself is sketchy and generally fine for this sort of book, their implementation within the layout and text is mostly just “waste of space”. There has not been a single page in the book which I felt was improved by the inclusion of art in it and so that made the art feel peripheral and sort of just solved in, rather than an actual contributing element to the overall quality of the book.

Beyond these minor quibbles though there is not much really bad with the book. For me at least these were, at best, minor irritants rather than something that actively made me unable to read the book.

Conclusion

I would say this book does a very successful job at what it attempts to do - act as a primer and instructional text for how to play in the so-called wargaming way. I have found a lot of useful ideas and approaches in the book that I’ve either implemented in my own games or am considering for future ones. There’s also been several things that I don’t really agree with and so would not use. I’ve not really mentioned those here though, because to me this isn’t a problem with the text itself, simply a difference in opinion on playstyle.

My conclusion to this is simple - this is a good text and I think most people who play or run OSR games should read it, if for no other reason than to simply see another similar approach to this style of play.